Anatomy and Function of the prostate

(Compiled July 2018)

What is it?

The prostate is a small gland about the size and shape of a walnut. It is part of a man’s internal sex organs. All the sex organs play a role in reproduction. The prostate generally increases in size as men age.

Where is it?

It is situated under the bladder and surrounds the urethra which is the tube that transports urine from the bladder to the penis where the urine is released through the ureter. This why problems with the prostate often affect the ability to urinate, causing what doctors call (urinary symptoms).

The rectum sits directly behind the prostate. This means that a part of the prostate can be felt if a finger is inserted up the rectum. (digital rectal examination) or the “finger” test. The tube that carries the semen from the testicles feeds into the ejaculatory ducts which then connect to the seminal vesicles which are just above the prostate. When prostate cancer spreads it often spreads first into these structures that surround the prostate. The prostate has gland tissue and smooth muscles fibres which help it to contract when a man ejaculates. The prostate is surrounded by a loose capsule which is connected to sheaths of pelvic muscles. Before 1981 surgeons were not aware of the nerve bundles towards the back and sides of the prostate that play an important role in erections. The identification of these nerves led to the first “nerve sparing” prostatectomy in 1982. Knowing where these nerves are situated has made a big difference to minimising erectile dysfunction in men who have had a prostatectomy.

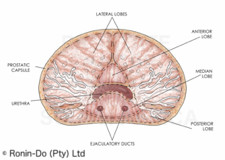

Until a few years ago, doctors described the different parts or areas of the prostate as lobes (see illustration below). One method of staging prostate cancer was to determine which lobes had been affected by cancer cells.

A more up-to-date way of describing the different areas of the prostate is the Zonal System. (See illustration below). 80 to 85% of prostate cancers start in the peripheral zone.

What does it do?

The prostate gland produces prostatic fluid which makes up about 15 to 30% of the semen or ejaculate. The average amount of semen ejaculated is 3.4ml which is less than a teaspoon full. Sperm make-up only 1 to 5% of the total volume of the ejaculate. The secretions from the seminal vesicles make-up the majority of the ejaculate. The secretions from the various glands that help to produce semen all assist with nourishing and protecting the sperm so that they can survive and impregnate an egg in the process of reproduction.

References

(1) Nicholas J., Primer on Prostate Cancer-2014, Springer Healthcare 2014.

(2) William K, Hurwitz M, D’Amico AV, et al. Biology of Prostate Cancer. Holland-Frei Cancer Medicine. 6th edition. Hamilton (ON): BC Decker; 2003. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK13217/

(3) Owen DH., Katz DF. A Review of the Physical and Chemical Properties of Human Semen and the Formulation of a Semen Simulant. J Androl 2005;26:459–469.

How common is Prostate Cancer in South Africa?

(Compiled February 2019)

According to Globcan, prostate cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer among men in over one‐half the countries of the world including the Americas, Northern and Western Europe, Australia/New Zealand, and much of Sub‐Saharan Africa. It is the leading cause of cancer death among men in 46 countries, particularly in Sub‐Saharan Africa and the Caribbean. (1a)

Although there are no reliable statistics on the incidence of prostate cancer amongst South African men, it is possible to get an idea of how common prostate cancer is in South African men by looking at the data from countries where men have reasonable access to screening for prostate cancer and where there is a significant population of black men with African ancestry. (Race is a proven risk factor for prostate cancer with black American and Jamaican men of African descent having the highest recorded rates of prostate cancer worldwide). (2a)

In the USA approximately 11.2 percent of all men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer at some point during their lifetime according to The SEER data from the National Cancer institute. (3) However if we compare the rates of prostate cancer in white vs black African American men there is a significant difference. It is estimated that 1 in 6 black African American men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer in their lifetime compared with 1 in 8 white American men. (2b) If we look at the data from 2008 to 2012 it showed that Black African American men had a 70% greater chance of being diagnosed with prostate cancer than white American men. (2c) They were also more than twice as likely to die from prostate cancer as their white counterparts, although this has improved in recent years.(2d)

One major advantage that black American men have over black South African men is that they are more likely to be diagnosed when the cancer is at a local or regional stage.(2e) (In other words, before it has spread to other parts of the body). This means that after 5 years most of these men will still be alive. In South Africa, the majority of black men will only be diagnosed when the cancer has spread, this is called metastatic prostate cancer and it is incurable.4 This means that after 5 years only about 30% of these men will still be alive. (5) Black African men from Southern Africa appear to have an additional disadvantage in that they present with significantly more aggressive prostate cancer than African Americans. (1b)

According to Prostate Cancer UK, 1 in 8 men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer at some point in their lives(6a) and for black British men of African descent 1 in 4 men can expect to be affected. (6b)

We recommend that black South African men consider screening from the age of 40 and that other ethnic groups start screening from 45.

Prostate cancer is more common in men with a family history of prostate cancer. If you have a family history of prostate cancer you are twice more likely to get prostate cancer. Having a brother with prostate cancer appears to put you at a higher risk than if you have a father with prostate cancer. The more family members affected by prostate cancer the more likely you are to get it. (7)

There is some evidence showing that prostate cancer is also more common in men who have a first degree relative who has been diagnosed with breast cancer, particularly when the breast cancer was diagnosed before the age of 50. (8) Men who have a daughter who has been diagnosed with breast cancer have a higher risk for aggressive prostate cancer.

We recommend that men with a family history of prostate or breast cancer in a first degree relative consider screening from the age of 40.

Conclusion

- Based on current USA and UK data and various clinical studies:

- About 1 in 8 to 1 in 9 white South African men are likely to be affected by prostate cancer.

- As life expectancy amongst black South African men increases, between 1 in 4 and 1 in 6 men are likely to be affected by prostate cancer. Black men are more likely to get prostate cancer at a younger age and a more aggressive type of prostate cancer.

- Prostate cancer is more common in men with a family history of breast and prostate cancer.

- Men who are at increased risk for prostate cancer because of their race or family history should consider screening for prostate cancer from the age of 40

- All other men should consider screening from the age of 45

Ref 1 Bray F et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. Ca: A journal for Clinicians. Vol 68 no. 10 Nov/Dec 2018 Available at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.3322/caac.21492

Ref 2 Ref DeSantis CE, Siegel RL et al. Cancer Statistics for African Americans,2016: Progress and Opportunities in Reducing Racial Disparities. 2016: CA cancer J Clin 2016;66:290–308

Ref 3 National Cancer Institute. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Available at: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/prost.html

Ref 4 Le Roux HA et al. Prostate Cancer at a regional hospital in South Africa: we are only seeing the tip of the iceberg. S Afr J Surg Vol. 53 no. 3&4. Dec 2015

Ref 5 Kirby RS, Patel M. Fast Facts: Prostate Cancer. Eight Edition 2014. Health Press Limited

Ref 6 Prostate Cancer UK. Are you at risk? Available at: https://prostatecanceruk.org/prostate-information/are-you-at-risk

Ref 7 Kicin´ski1 M, Vangronsveld J. An Epidemiological Reappraisal of the Familial Aggregation of Prostate Cancer: Available at: www.plosone.org Plos One. October 2011 | Volume 6 | Issue 10 | e27130

Ref 8 Lamy P. Trétarre B et al. Family history of breast cancer increases the risk of prostate cancer: results from the EPICAP study. Oncotarget, 2018, Vol. 9, (No. 34), pp: 23661-23669

Risk Factors for Prostate Cancer

(Compiled July 2018) (Revised January 2019)

The best known and proven risk factors for prostate cancer are advancing age, race and a positive family history of prostate cancer. There are other risk factors but there is less evidence for these.

Age

As men get older they are more likely to get prostate cancer. The risk for prostate cancer begins to rise sharply after age 55 years and peaks at age 70–74. Global statistics show that three quarters of prostate cancer occur in men over the age of 65 and that prostate cancer is rare in men below the age of 50. However it is important to note that black African men tend to get prostate cancer at a younger age. (See section on race and prostate cancer)

Race

In the USA the risk of prostate cancer is 60% higher in black American men compared to white males. The risk of dying of prostate cancer amongst Black African American men is also twice as high as that of white American men. The current statistics in South Africa are unreliable for a number of reasons but based on the studies from the USA and the UK we believe that black African men are at a much higher risk of getting prostate cancer than other race groups. The type of prostate cancer that they get is also is also likely to be more aggressive and to be passed on genetically.

Family history

There is strong evidence to show that a family history of prostate cancer increases a man’s risk of prostate cancer. Men who have a father or brother with prostate cancer are 2 to 3 times more likely to get prostate cancer themselves. The number of relatives with prostate cancer and their age at diagnosis is also important in terms of the likelihood of being affected at a younger age. Some studies show that having a mother or daughter who has had breast cancer also increases a man’s risk for prostate cancer.

References: Gann PH., Reviews in Urology. Vol 4, suppl. 5 2002

Other Modifiable Risk Factors for Prostate Cancer

Sexual Activity

There is strong evidence to suggest that men who have more frequent ejaculations (more than 21 a month), throughout their adult life are about 20% less likely to get prostate cancer. The ejaculations can be from sex, masturbation or nocturnal emissions.

Ref: Rider, Jennifer R. et al. Ejaculation Frequency and Risk of Prostate Cancer: Updated Results with an Additional Decade of Follow-up. European Urology , Volume 70 , Issue 6 , 974 – 982

Smoking

It is unclear whether smoking increases the risk for prostate cancer. However, there is data that shows that smokers have a 17% greater risk of dying from prostate cancer than non-smokers. Smoking greatly increases the risk of many other cancers so it’s worthwhile for men who smoke to quit.

Ref: Huncharek, Michael et al. Smoking as a Risk Factor for Prostate Cancer: A Meta-Analysis of 24 Prospective Cohort Studies. American Journal of Public Health 100.4 (2010): 693–701. PMC. Web. 20 June 2018.

Obesity

The relationship between obesity and prostate cancer is a complicated one. It is more difficult to detect prostate cancer in obese men for a number of reasons:

- They tend to have lower PSA scores

- They have larger prostates which mean that more cancers are likely to be missed when doctors perform a biopsy

- It is more difficult to perform a digital rectal examination on an obese man

All this means that prostate cancer is less likely to be detected in the early stages in obese men. Obesity is also associated with an increased risk for aggressive prostate cancer and a poorer outcome in men who are treated for prostate cancer. There is strong evidence linking obesity to a number of other serious diseases and for this reason we recommend that obese men get medical assistance to help them get there weight under control.

Ref: Allott, Emma H. et al. Obesity and Prostate Cancer: Weighing the Evidence. European Urology, Volume 63 , Issue 5 , 800 – 809

Dietary factors and prostate cancer

It is important to note that the evidence linking certain foods and vitamins to prostate cancer is not conclusive. We recommend that men follow a diet that has been proven to be good for overall health. Men should also be cautioned about the use of supplements to prevent prostate cancer as there is a possibility that some supplements could increase the risk. The following are some findings that will require additional research before the results can be considered conclusive and recommendations can be made. Please note that the evidence is not currently strong enough for these so we cannot make recommendations.

Saturated Fats

There is some evidence to show that the regular intake of saturated fats can increase the risk of prostate cancer. Saturated fats are animal fats found mostly mainly in dairy products and red meat.

Meat cooked at high temperatures

There is some evidence to show that eating meat that is well-done or meat that is cooked at a high temperature (e.g. grilled, fried, and barbecued meats) increases the risk for advanced prostate cancer. The more of this type of meat that is eaten the greater the risk.

Calcium

There is some evidence to show that a diet that is high in calcium increases the risk for prostate cancer.

Vegetables

A diet that includes plenty of fresh fruit and vegetables has strong health benefits and some of the components found in vegetables have antioxidant properties which may help to reduce the risk for cancer.

Lycopene

There is some evidence to show that lycopene can reduce the risk for prostate cancer through its antioxidant effect. Lycopene is a substance that is found in various foods. Foods containing high amounts of lycopene include cooked tomatoes and tomato based products like tomato sauce and tomato paste, guavas, watermelon, grapefruit, papaya, sweet red peppers, asparagus red cabbage and mangoes. However, to obtain significant levels of lycopene from tomatoes products like tomato paste are required as raw tomatoes have very low levels. To illustrate this, one slice of raw tomato contains 515 micrograms of lycopene whilst 2 tablespoons of tomato paste contains 13 800 micrograms. Cooking also alters the lycopene’s molecular structure so that it is more easily absorbed by the body.

Vitamin E

There is some evidence that taking a vitamin E supplement may increase the risk for prostate cancer.

References for Dietary Factors and Prostate Cancer

(1) Gathirua-Mwangi et al. Dietary factors and risk for advanced prostate cancer. European Journal of Cancer Prevention. 23(2):96–109, MAR 2014

(2) Ref: Ford N., Livestrong.com. Accessed on 30/06/2018. Available at: https://www.livestrong.com/article/344493-tomato-cooked-or-raw-lycopene/

(3) Ref: Gann PH. Risk factors for prostate cancer. Reviews in Urology. Vol 4, suppl. 5 2002.

(4) Klein EA et al. Vitamin E and the risk of prostate cancer: Updated results of the selenium and vitamin E cancer prevention trial (SELECT). JAMA. 2011 October 12; 306(14): 1549–1556. doi:10.1001/jama.2011.1437.

Alcohol and Prostate Cancer

There is strong evidence showing that alcohol increases the risk for mouth, throat, oesophageal, liver and colorectal cancer. (1) However the link between alcohol consumption and prostate cancer is less clear and studies have shown conflicting results. We cannot therefore make recommendations based on the current research.

Some evidence shows that men who are heavy regular drinkers and binge drinkers are at increased risk for prostate cancer whilst non-drinkers may be at increased of dying from prostate cancer compared to those who are light users of alcohol. (2)

Other studies show that alcohol consumption is not associated with overall prostate cancer risk or risk for low-grade prostate cancer but that the risk for high-grade prostate cancer is increased in men who consumed a minimum of seven drinks per week when aged 15 to 19 years compared with men who did not drink during that period of their lives. The same study showed that men with a higher cumulative alcohol intake throughout their lives were more likely to be diagnosed with high-grade prostate cancer. (3)

References for Alcohol and Prostate Cancer:

Ref (1) Testino G, Maedica. A Journal of Clinical Medicine, Volume 6 No.4 2011.

Ref (2) Dickerman A et al. Alcohol intake, drinking patterns, and prostate cancer risk and mortality: A 30-year prospective cohort study of Finnish twins. Cancer Causes Control. 2016 September ; 27(9): 1049–1058. doi:10.1007/s10552-016-0778-6.

Ref (3) Michael J, et. Cancer Prev Res. 2018; Early-Life Alcohol Intake and High-Grade Prostate Cancer: Results from an Equal-Access, Racially Diverse Biopsy Cohort. Available at http://cancerpreventionresearch.aacrjournals.org/content/early/2018/08/16/1940-6207.CAPR-18-0057

Symptoms of prostate cancer

(compiled June 2019)

There are generally no symptoms of prostate cancer in the early stages of the disease which is why screening is so important. Some of the symptoms of prostate cancer are the same as the symptoms for an enlarged prostate (benign prostatic hyperplasia or BPH). This condition is also common in older men.

Symptoms in Early (localised) Prostate Cancer

Localised prostate cancer is when the cancer is contained within the prostate. There are generally no symptoms at this stage which is why screening is so important.

Symptoms for locally Advanced Prostate Cancer

At this stage the cancer tumour may have spread to areas surrounding the prostate such as the bladder, the pelvic nerves, the urethra and the seminal vesicles. The tubes carrying the urine (ureters) can be blocked. The following symptoms can occur:

- A need to urinate frequently, especially at night

- An urgent need to urinate

- Difficulty starting urination or holding it in

- Weak or interrupted flow of urine

- Painful urination

- Blood in the urine or semen

- Erectile dysfunction

- Loin pain

- Very little or no urine

- When the tumour enlarges it can push against the rectum which sits behind the prostate causing constipation, cramping and rectal bleeding.

Symptoms for Advanced Prostate Cancer (Metastatic Prostate Cancer)

When prostate cancer spreads to other body parts it may cause:

- Bone pain particularly in the pelvis and lower spine due to bone metastases (cancer tumours that develop in the bones)

- Bone fractures

- Spinal cord compression causing a loss of feeling in the limbs

- Lymph node enlargements

- Loin pain due to a blockage in the tubes carrying urine from the kidneys to the bladder

Other symptoms that occur when the cancer is spread widely throughout the body can include:

- Lack of energy from iron loss (anaemia)

- Weight loss with muscle wasting and loss of appetite

References 1 – Kirby RS, Patel M. Fast Facts: Prostate Cancer. Eight Edition 2014. Health Press Limited

Screening for prostate cancer

(Updated 25 June 2024)

What screening tests are recommended?

For men who are not experiencing any symptoms, a Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA) blood test is the recommended first line test. The rapid PSA test is not recommended as a screening test for prostate cancer as it does not use age related reference ranges.

Before deciding on whether to go for prostate cancer screening you should understand the following:

- Disadvantages of screening

The PSA blood test is not a cancer specific test. In about 75 out of 100 cases when the PSA is raised there is no prostate cancer which means that something other than cancer has caused it to be higher than normal (false positive). This may cause unnecessary anxiety in men. An enlarged prostate is often the cause of a slightly higher than normal PSA score.

– In about 15 out of every 100 men who have a normal PSA there is prostate cancer (false-negative result). This may cause men who have had a PSA to believe that they are cancer free when in fact they have prostate cancer.

– The PSA test may detect a type of prostate cancer that is slow-growing and non-aggressive and that may never cause a problem. Men with this type of prostate cancer who opt for active treatment may be worse off because of the side effects of treatment which negatively affect their quality of life. However, “active surveillance” can avoid over-treatment in men with low risk for disease progression. - Advantages of screening

– Men who don’t go for screening could end up with prostate cancer that has spread (metastatic prostate cancer) and which can never be cured. The treatments for metastatic prostate cancer have a major impact on a man’s quality of life as they involve removing testosterone (the male hormone) from the body.

– Screening can help detect prostate cancer in the early stages when it can be cured. Early detection of prostate cancer reduces the risk of dying from prostate cancer by up to 56%.

– Screening can reduce anxiety if the screening results are negative.

At what age should South African men consider going for screening?

Informed patient-based screening is recommended in men with a life expectancy of more than 10 years in the following situations:

– From the age of 40 in black African men and in men who have a family history of prostate and/or breast cancer in a first degree relative.

– From the age of 45 years for all other men

– In men who have undergone genetic testing and who are carriers of prostate cancer risk germline mutations, screening should be done at age 40 or at 10 years younger than the age of onset of the youngest affected family member if this is before 40

Germline mutations that increase the risk for prostate cancer include: BRCA2, BRCA 1, HOXB13, ATM, CHEK2, PALB2, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, EPCAM and TP53 genes.

In addition, patients with a history of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and/or clinical suspicion of prostate cancer, regardless of age group, should have their PSA tested.

Recommended screening intervals

Men with a low initial PSA level (PSA ≤1.0 ng/mL) can screen every two years and those with higher levels should screen annually.

Due to their increased risk for PCa, Black African men should consider screening annually.

Men with a mutation in a PCa-associated gene, or a strong family history of PCa should screen annually.

The Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA) test

Prostate specific antigen is a type of protein that enters the blood when the barriers in the prostate are damaged. It is a simple blood test that gives an indication of whether something is wrong with your prostate. It is not a cancer specific test. A high PSA test result could be caused by:

– an enlarged prostate

– an infection/inflammation of the prostate (prostatitis)

– prostate cancer

Avoid the following activities for 48 hours before a PSA test:

– cycling

– ejaculation

Your PSA result may not be accurate:

- if you have an active urinary tract infection

- after recent urinary tract instrumentation and/or urinary retention

- if you have had a prostate biopsy in the previous 6 weeks

- if you are taking medication such a finasteride or dutasteride for an enlarged prostate or hair loss (5-alpha reductase inhibitor)

Normal PSA Scores

The most common threshold used to define a high PSA is ≥4 ng/mL. The use of age-related references improves detection rates and it is therefore recommended rather than using the traditional threshold of 4 ng/mL.

• 40 – 50 years 0 – 2.5 ng/mL

• 50 – 60 years 0 – 3.5 ng/mL

• >60 years 0 – 4.0 ng/mL

Chances of having prostate cancer diagnosed for a PSA ≥4.0 ng/mL is approximately 25%

Chances of having prostate cancer diagnosed for a PSA ≥10 ng/mL is approximately 60%

Measuring Free PSA

This is a variation of the normal PSA test that is used to distinguish between men who have an enlarged prostate as opposed to prostate cancer. It measures PSA that is not bound to protein in the serum.

PSA Velocity

If you have been having regular PSA tests over 1 to 2 years and there are more than 3 test results available your doctor may also check to see how much the PSA score has changed over time and how quickly it has risen. If the PSA changes by more than 0.75ng/ml in a year, this can give an indication of potential prostate cancer even though the score is still within the normal range.

The Digital Rectal Examination (DRE)

The digital rectal examination is no longer considered necessary to screen for prostate cancer in men who are not experiencing symptoms, and who have a PSA that falls within the normal range for their age.

What happens if your PSA is high ?

If your PSA is high it will often be retested. If it is still high you will generally be referred to a urologist for further investigation.

The urologist will perform a full assessment to determine the reason for the raised PSA.

This will include a digital rectal A lot of men are embarrassed about this test but it is quick and there are only a few seconds of minor discomfort. The examining doctor inserts a gloved and lubricated finger into the rectum so that they can feel the prostate for any abnormal lumps, hardening, asymmetry or a lack of mobility.

If your urologist suspects prostate cancer you may be referred for a special type of MRI scan called a multiparametric MRI scan.

A prostate biopsy is used to diagnose prostate cancer. A biopsy involves inserting a number of needles into the prostate in order to obtain a small sample of the prostate cells which are then sent to a laboratory to be checked for cancer.

References

(1) Advising men aged 50 and over about the PSA test for prostate cancer: information for GPs. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/prostate-specific-antigen-testing-explanation-and-implementation Last accessed on 5 October 2019.

(2) Kirby RS, Patel I. Fast Facts: Prostate Cancer. Eighth edition. Health Press Limited. Jan 2014

(3) Hoffman RM. Screening for prostate cancer. Available on: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/screening-for-prostate-cancer Last accessed 24 July 2019

(4) South African Prostate Cancer Guidelines June 2024

Prostate Biopsy and Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Updated on 25 June 2024

If your PSA test is high, or your doctor felt anything abnormal when doing a digital rectal examination, or you have other signs and symptoms of prostate cancer you will be referred to a urologist for further examination. The urologist will take a thorough history. It is important to advise your urologist of any family history of prostate, breast and other cancers. A digital rectal examination will be performed to feel for any signs of prostate cancer.

Your urologist may do a number of other tests to decide whether a prostate biopsy is necessary.

Multiparametric Magnetic Resonance Imaging (mp-MRI) (1) (2) (3)

Since its introduction, this technology has made a huge difference to the field of prostate cancer diagnosis. It is recommended that an mpMRI is performed before a biopsy. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) uses a strong magnetic field, radio waves, and special computer software to show detailed images of the prostate and anything unusual in it, or around it. The size, shape and location of tumours can be identified, which assists with staging and gives an indication of how aggressive the cancer is. MRI also has the advantage of being non-invasive and there is no exposure to radiation. It is done at a radiology facility and the results are interpreted by a radiologist. An MRI also helps the urologist to identify areas that need to be targeted for the biopsy. Up to four different parameters may be used to check for cancer cells when doing a prostate MRI.

Parameter 1 – T2 weighted MRI (T2 MRI)

This gives a 3D map of prostate zone anatomy and identifies suspicious looking areas.

Parameter 2 – Diffusion weighted imaging (DWI MRI)

This shows the movement of water molecules in tissue which helps to identify cancer cells which restrict the motion of water

Parameter 3 – Dynamic contrast enhanced imaging (DCE MRI)

Here a contrast agent is injected into a vein and it shows the blood flow in the tumour which is different to blood flow in normal tissue.

Spectroscopy (MRI-S) may be added as a fourth parameter.

This procedure identifies cancer cells by the chemical metabolites that they produce which are different from normal cells.

A Prostate Biopsy

This is the procedure that is used to diagnose prostate cancer. It involves extracting tissue samples from the prostate using special thin hollow biopsy needles. A prostate biopsy is usually done using an ultrasound probe inserted in the rectum which provides a live image of the prostate. This enables the urologist to see where the biopsy needles are being inserted, so that samples of tissue can be taken from different areas within the prostate. The samples are then sent to a pathology laboratory where the cells from each needle (core) are examined and graded according to how badly the cancer has affected the tissue. This grading is called a Gleason score is covered in the section “Understanding Your Laboratory Results from a Prostate biopsy.” This is called a histological diagnosis. It’s important to understand that no biopsy is 100% reliable as the needles may miss the tumour, particularly if it is very small or if the prostate is large.

Types of prostate biopsies

Random Systematic 12-core sextant biopsy (SBx)

In this procedure transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) imaging is used to visualize the prostate gland. This involves inserting an ultrasound probe up the rectum which then provides a live image of the prostate and helps the urologist to guide the biopsy needles into different parts of the prostate. Normally 12 to 14 needles (referred to as cores) are then inserted systematically into different parts of the prostate. With this method about one third of clinically significant prostate cancers will be missed. In men who have large prostates the percentage of prostate tissue that is sampled is naturally lower and the results are therefore less reliable.

MRI Targeted Biopsies

A greater number of prostate cancers can be diagnosed through the MRI targeted biopsy procedure and this therefore the recommended option when available. They also help urologists to detect more of the problematic prostate cancers (clinically significant cancers that are likely to progress) and less of the non-problematic cancers.

A Cognitive Prostate Biopsy

This has become the preferred method for many urologists who routinely do an MRI before the biopsy as it does not require any additional equipment. If you have had an MRI before the biopsy then the urologist will review the MRI images before and during the biopsy and use the information to guide where best to take samples from within the prostate. The success of this technique is very much dependent on the urologist’s ability to translate MRI images to transrectal ultrasound without a physical overlay of the two images (operator dependant). Cognitive fusion biopsies have a higher detection rate than random biopsies.

MRI/TRUS Fusion Guided Biopsy

New technology is now available to combine or “fuse” MRI images with the live imaging from transrectal ultrasound. This MRI/TRUS fusion technology involves the use of sophisticated software to combine the two images. Remember that the MRI provides a clear image of where the “area of interest” in the prostate is, so with this technology the urologist can guide the biopsy needles directly to the potential tumour. This means that fewer needles will need to be used. This technology is still very new in South Africa and urologists that use this technique require additional training, but the results are less “operator dependant” than a cognitive biopsy. This biopsy method is particularly useful for patients who continue to have a high PSA or suspicious DRE but who have a negative biopsy result using the random biopsy method.

There are two routes that urologists use for performing a biopsy:

Transperineal biopsy

In a transperineal biopsy, the needles are inserted through the perineum (the area between the scrotum & the anus) after a small cut is made. There is less risk of infection with this procedure compared to a transrectal biopsy and it is therefore the recommended biopsy method. The procedure is however more painful than a transrectal biopsy.

Transrectal biopsy

In a transrectal biopsy the needles are inserted through the rectum. There is a higher risk of infection from transrectal biopsies as bacteria from the rectum can be transferred via the biopsy needle to the urinary tract, blood circulation and the prostate. There is also a higher risk of bleeding.

Some urologists require their patients to use an enema to empty the bowels of all faeces before the procedure. An antibiotic is always used to help prevent infections. It’s important to tell your doctor if you are taking any medications that can increase the risk of bleeding such as; warfarin, aspirin, ibuprofen or any other type of anticoagulant including natural herbal products. Your doctor will advise you when to stop taking these medications to prevent excessive bleeding from the procedure.

Anaesthetic

The procedure may be performed under general anaesthetic or whilst you are awake using local anaesthetic.

After the procedure

You may have some pain and bleeding from your rectum if you had a transrectal biopsy or from the perineal area if you had a transperineal biopsy.

There may be blood in your urine, stools and semen for a few days after the procedure. See your doctor if you experience any of the following symptoms:

- a fever

- difficulty urinating

- prolonged or heavy bleeding

- increasing pain

References

Ref 1 – Kirby RS, Patel M. Fast Facts: Prostate Cancer. Eight Edition 2014. Health Press Limited

Ref 2 – De Visschere PJ, Briganti A, Fütterer JJ, et al. Role of multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging in early detection of prostate cancer. Insights Imaging. 2016;7(2):205-14.

Ref 3 – Brown EM et al. Recent advances in image-guided targeted prostate biopsy. Abdom Imaging. 2015 August ; 40(6): 1788–1799

Ref 4 – Andrea B et al. The Role of MRI-TRUS Fusion Biopsy in the Diagnosis of Clinical Significant Prostate Cancer (CsPca)

Ref 5 – Xiang J. Transperineal versus transrectal prostate biopsy in the diagnosis of prostate cancer:

a systematic review and meta-analysis. World Journal of Surgical Oncology (2019) 17:31

Understanding Your Biopsy Results and Gleason Score

Compiled 20 Jan 2020

Your pathology laboratory report after a prostate biopsy will provide key information as to how aggressive the cancer is. Understanding your results will help you to make an informed decision about the treatment options available to you.

Your laboratory results will include a Gleason score which is one of the most important indicators of how aggressive the prostate cancer is and what treatment options will be suitable. 1However, it needs to be interpreted together with your other test results. Always get a copy of your laboratory report as it contains critical information that you will need if you wish to get a second opinion or if you want to do any research of your own about your diagnosis. You need to be aware that it is possible that a negative biopsy report doesn’t rule out the possibility that you may have prostate cancer.1

Each needle (core) obtained from a biopsy is analysed separately and the pattern of the tissue in each core is given a separate diagnosis. 2The pathologist assigns a grade between 1 and 5 to each sample. A grade 1 pattern when viewed under a microscope looks most like normal tissue and a grade 5 pattern is the worst as the tissue appearance is very abnormal. 2 Although grades 1 and 2 appear different, they are now reported as a grade 3 as they have the same outcomes. A pure grade 3 cancer is unlikely to ever metastasize.3

The overall number of cores (biopsy needles) that are positive for cancer and the percentage of each core that is made up of cancer, gives an indication of the tumour size.

How is a Gleason Score Calculated?

The Gleason score is most often obtained by adding the number of the most common Gleason pattern with the second most common. The lower the score the less aggressive the cancer and the less likely it is to progress. The exception to this is if any one of the cores contains a lot of high-grade cancer, or there are 3 grades that include high-grade cancer. In these two instances the Gleason score is modified to show the aggressive nature of the cancer so that the most suitable treatment options can be selected.2 Gleason scores of 1 and 2 are now reported as a Gleason 3 as cancer with these patterns has an outcome no different from grade 3. 3

It is important when interpreting a Gleason score to understand that the order of the numbers is highly significant as the first number is always the most prevalent type of pattern found. So even if the total is 7, a Gleason score of 4 + 3 = 7 is worse than a Gleason score of 3 + 4 = 7. That’s because 4 indicates a more aggressive cancer so if it is the most prominent in all of the cores, that’s worse than if 3 was the most prominent. 2

What do different Gleason scores mean?

If there are multiple cores with different grades they will be reported separately and ideally by anatomical site.3Prostate cancer can have areas with different grades. To get a total Gleason score the pathologist will use the grades from the 2 areas that make up most of the cancer. 2

Gleason 6– Is considered low grade. The lowest score from cancer found on a biopsy is 6. These cancers are most often non-aggressive and slow growing.2Many insurance companies will not pay out for dread disease cover for a Gleason 6 score.

Gleason 7 is considered intermediate risk but there is a difference:1

Gleason 3+4 = 7 Cancers with this grade still have a good outlook (prognosis), but not as good as a Gleason 6

Gleason 4+3 = 7 Cancers with this grade are more likely to grow and spread than a 3+4=7

but not as much as a Gleason 82 1

Gleason 8 – This is considered a high grade cancer1

Gleason 9 to 10 These are also high grade cancers but are twice as likely as a Gleason 8 to grow and spread quickly 2

A new system has now been developed which makes it a lot easier to understand the Gleason score and how high risk the prostate cancer is. The Gleason scores are reported in Grade Groups as per the table below.2

International Society of Urological Pathology 2014 grade (group) system

| Gleason score | ISUP grade |

| 2-6 | 1 |

| 7 (3+4) | 2 |

| 7 (4+3) | 3 |

| 8 (4+4 or 3+5 or 5+3) | 4 |

| 9-10 (4+5 or 5+4 or 5+5) | 5 |

Some of the other things that may be reported on your pathology report:

Adenocarcinoma

This is the most common type of cancer found in the glandular cells of the prostate

Perineural invasion2

This means cancer was seen alongside a nerve fibre within the prostate and that the cancer has possibly spread outside of the prostate.

Prostatic Intraepithelial Neoplasia (PIN) and Atypical Small Acinar Proliferation (ASAP 1 2

PIN indicates that there are irregular abnormal cells. Although they are not currently cancerous, high grade PIN is very similar to cancer cells and can be an indication that cancer may be present in other parts of the prostate.

Acute inflammation (acute prostatitis) or chronic inflammation (chronic prostatitis)2

Prostatitis is inflammation of the prostate. It doesn’t affect the cancer diagnosis

Atrophy, adenosis or atypical adenomatous hyperplasia?2

These are types of conditions of the tissues that can be seen by the pathologist when examining the biopsy samples. They are non-cancerous.

Seminal vesicle2

This is another gland, that like the prostate, makes up part of the seminal fluid. There are two that are situated just behind the prostate and when prostate cancer spreads it is often to one or both of the seminal vesicles. Sometimes, a biopsy sample will have been taken from the seminal vesicles.

Atypical glands, atypical small acinar proliferation (ASAP), glandular atypia, or atypical glandular proliferation2

These are patterns that could potentially be cancer but are not clear enough to be graded.

References:

Ref 1 – TRUS and biopsy results. Prostate Cancer UK. Available at: https://prostatecanceruk.org/for-health-professionals/online-learning

Ref 2 – Understanding Your Pathology Report: Prostate Cancer. Association of Directors of Anatomic and Surgical Pathology. American Cancer Society. Last reviewed March 2017. Available at: https://www.cancer.org/treatment/understanding-your-diagnosis/tests/understanding-your-pathology-report/prostate-pathology/prostate-cancer-pathology.html

Ref 3 – Iczkowski K. Grading (Gleason). PathologyOutlines.com, Inc. Available at: http://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/prostategrading.html Updated June 2016

Tests to detect if prostate cancer has spread

Compiled April 2020

If your doctor suspects that the prostate cancer has spread to other parts of your body you may be referred for additional tests. Once prostate cancer spreads out of the prostate it spreads to surrounding tissues and structures. The cancer cells can then enter the blood and lymph vessels and spread throughout the body to bone and soft tissue, where they re-implant and grow to form secondary tumours or metastases. These metastases are still made up of prostate cancer cells.

It is important for your doctor to know whether the prostate cancer has spread outside of the prostate and if so where. This helps with staging and planning the treatment.

If the cancer recurs after treatment, imaging tests may be required to determine where the cancer has spread to in order to plan further treatment.

Some tests are better than others at finding metastases in different tissues which is why your doctor may order more than one type of test. Not all tests may be available at all facilities and some tests are very expensive. No test is 100% accurate and initially the cancer cells that spread might be very small (micro metastases) and therefore undetectable by some tests.

Most tests will be done at a radiology/nuclear medicine facility. The test results will be analysed by a radiologist/nuclear physician (a medical doctor who specialises in the diagnosis of diseases and injuries using medical imaging). The tests are normally done by a radiographer who works under the supervision of a radiologist. Some tests require that you have an injection with a radioactive dye. It’s important to tell the healthcare workers if you have any allergies.

Tests to detect if cancer has spread to lymph nodes

Prostate cancer tends to spread first to regional lymph nodes in the pelvic area. Lymph nodes are part of the lymphatic system. The lymphatic system consists of lymph vessels and lymph nodes and is part of the body’s immune system. The lymph vessels carry lymph fluid, which contains nutrients and other substances, to the body’s tissue cells. Lymph vessels also remove and transport damaged cells, cancer cells, bacteria and viruses from tissues. These are then filtered out when the lymph fluid travels through the lymph nodes which are like filters. The cancer cells can also grow inside the lymph nodes. The following test may be used to determine if any lymph nodes have been affected.

CT

MRI

PET -CT/MRI (PSMA, Choline)

SPECT-CT (Tc-99m PSMA)

Tests to detect if cancer has spread to bone (bone metastases)

Prostate cancer commonly spreads to bones. It will often first spread to the bones in the pelvis and lower spine. The cancer can affect bones by activating cells in the bone resulting in abnormal bone production. This results in abnormal build-up of bone and the formation of osteoblastic lesions. The cancer can also cause abnormal destruction of bone causing osteolytic lesions. This is important because tests that are good at detecting osteoblastic lesions may not be good at finding osteolytic lesions. Some patients may have a mixture of both types of lesions. The following tests may be used to check for bone metastases:

Standard X-rays

Bone scan (this test is increasingly being replaced by newer tests that are far more accurate)

Especially when prostate cancer recurs or PSA is low – PET/CT or MRI

For patients who have undergone a radical prostatectomy – PSMA PET/CT or SPECT-CT

Tests used to detect if cancer has spread to soft tissue other than lymph nodes (visceral metastases)

Prostate cancer can also spread to organs like the liver, digestive system, kidneys, adrenal glands and brain. These are called visceral metastases. Tests use to check if prostate cancer has spread to organs can include.

PET-CT/MRI

SPECT/CT (PSMA)

Whole body MRI (with diffusion-weighted imaging WB-MRI)

| Summary of Types of Tests used to check if prostate cancer has spread (metastasized) | What the Test Shows |

| X-Rays of the lower back and pelvis | Abnormal (hard)whitening of the tissue on bone (sclerotic metastases) or more rarely decreased whitening (osteolytic metastases) |

| Bone Scans

This is an older test with limited value particularly in men with a PSA <20 |

Bone scans show if the cancer has spread to the bones (bony metastases). |

| SPECT-CT | This is similar to a bone scan but provides a 3D image and can show lesions smaller than 1cm. It is more accurate than a traditional bone scan |

| CT (computed tomography)

PET CT/MRI (positron emission tomography /in combination withcomputed tomography /magnetic resonance imaging MRI Scans (magnetic resonance imaging) |

These scans show a slices through the body and can show cancer tumours (metastases), that have spread to different parts of the such as bone, lymph nodes, the liver and other organs

Whole body MRI may be more accurate than a bone or CT scan for identifying and measuring bony metastases |

| (PMSA) PET CT /MRI Scan prostate-specific membrane antigen positron emission tomography/computed tomography scan | This test may be the most sensitive compared to other imaging modalities as it has been shown to be able to identify metastases in patients even with very low PSA levels (most commonly used to detect if cancer cells have returned after treatment. It can detect lesions even if the PSA score is <0.5 ng/ml. |

| (T99m PMSA) SPECT/CT prostate-specific membrane antigen positron emission tomography/computed tomography scan | This test is similar to PSMA PET/CT but slightly less sensitive |

- Coetzee L. Metastatic Prostate Cancer. Health Press Limited 2017.2. Turpin A et al. Imaging for Metastasis in Prostate Cancer: A Review of the Literature. Front. Oncol. 10:55. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.00055. Available at www.frontiersin.org.

- Turpin A, (2020) Imaging for Metastasis in Prostate Cancer: A Review of the Literature. Front. Oncol. 10:55. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.00055

- Tabotta et al. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders (2019) 20:619. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-019-3001-6

- Futterer JJ et al. Imaging modalities in synchronous oligometastatic prostate cancer. World Journal of Urology 2018. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-018-2416-2

- Lengana T et al. Ga-PSMA PET/CT Replacing Bone Scan in the Initial Staging of Skeletal Metastasis in Prostate Cancer: A Fait Accompli? Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2018 Oct;16(5):392-401. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2018.07.009.

- Hofman MS et al . proPSMA Study Group Collaborators. Prostate-specific membrane antigen PET-CT in patients with high-risk prostate cancer before curative-intent surgery or radiotherapy (proPSMA): a prospective, randomised, multicentre study. Lancet. 2020 Apr 11;395(10231):1208-1216. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30314-7.

- Giesel FL et al. Detection Efficacy of (18)F-PSMA-1007 PET/CT in 251 Patients with Biochemical Recurrence of Prostate Cancer After Radical Prostatectomy. J Nucl Med. 2019 Mar;60(3):362-368. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.118.212233. Epub 2018 Jul 24. PubMed PMID: 30042163

Prostate Cancer Stage and Grade

It is important for your doctor to have an indication of the stage of your prostate cancer as this determines what treatment options are available to you.

Clinical staging

This is done before treatment is initiated and is based on the results of your digital rectal exam (DRE), your PSA score, Gleason grading and biopsy results. If any other investigations like an MRI, X-Rays, bone scans, CT and PET scans have been done, these will also help with staging.

Pathologic staging

If you have surgery to remove the prostate (a radical prostatectomy) your cancer will be restaged. This sentence doesn’tlead on logically from the one before -This is because the prostate and surrounding tissue removed during surgery including any affected lymph nodes are sent to a laboratory for analysis. This is more accurate than clinical staging. Pathologic staging is indicated by a ‘p’.

The laboratory report will also indicate whether the surgical margins were positive. The surgical margin is the edge of the tissue surrounding the removed tumour. Ideally,these should be free of any cancer cells (a negative margin). A positive surgical margin means that cancer cells were found by the pathologist at the edge of the removed tumour which could mean that not all of the cancerous tissue was removed.

The most common method to stage prostate cancer is the TNM method.

The information below is adapted from the AJCC Cancer Staging Handbook from the American Joint Committee on Cancer.

T – indicates the tumour size and how far it has spread

N – describes lymph node involvement

M – indicates whether or not the cancer has spread (metastasised) to bones or other organs

T- Tumour Staging (Clinical staging)

Stage T1

This is the earliest stage of prostate cancer and the cancer is usually slow growing

The tumour cannot be felt on DRE and it is not visible with imaging tests

PSA levels are usually low

T1a8

The tumour is usually found when prostate tissue is examined for other reasons (for example removal of prostate tissue due to an enlarged prostate)

Only 5% of the tissue sample examined has cancer

T1b8

The tumour is usually found when prostate tissue is examined for other reasons

The cancer is found in more than 5% of the tissue sample examined

T1c8

The tumour is identified by a needle biopsy which is done because of a raised PSA

Stage T2

There is increasing risk of the cancer growing and spreading

The cancer has not spread out of the prostate

PSA levels are usually low or medium

T2a

The tumour involves half of one lobe or less

The tumour cannot be felt on DRE

T2b

The tumour involves more than one half of one lobe but not both lobes

The tumour may be large enough to be felt on DRE

T2c

The tumour involves both lobes

The tumour may be large enough to be felt on DRE

Stage T3

The tumour has spread outside of the prostate capsule

The tumour is growing or the cancer is high grade

PSA levels are usually high

These are all indications of a locally advanced cancer that is likely to grow and spread

T3a

Tumour has spread outside of the prostate capsule on one or both sides

T3b

Tumour has spread outside of the prostate and invades one or both seminal vesicles

Stage T4

The tumour is fixed. 8This means that cancer cells have spread from the initial tumour in the prostate and haveattached to other tissue completely different from the prostate – normally the pelvic wall.

Or

the cancer invades structures outside of the prostate (other than the seminal vesicles) such as the; external sphincter, rectum, bladder, levator muscles and/or the pelvic wall.8

N-Staging (involvement of lymph nodes)

The lymphatic system consists of lymph vessels and lymph nodes and is part of the body’s immune system. The lymph vessels carry lymph fluid, which contains nutrients and other substances, to the body’s tissue cells. Lymph vessels also remove and transport damaged cells, cancer cells, bacteria and viruses from tissues. These are then filtered out when the lymph fluid travels through the lymph nodes which are like filters. The cancer cells can also grow inside the lymph nodes.

When cancer spreads (metastasizes) it is often first to the lymph nodes around the prostate. The cancer can also spread to lymph nodes further away from the prostate (distant lymph nodes), in which case the cancer is classified as metastatic prostate cancer.

The involvement of lymph nodes is an important part of the staging and is indicated by the letter ‘N’. If the distant lymph nodes are affected this will be indicated under the metastatic cancer classification (M).

N0

No regional lymph nodes affected by cancer

N1

The cancer has spread (metastasized) to the regional lymph nodes

M stage (Distant metastases)

The M staging describes whether or not the cancer has spread to other parts of the body not near the prostate and to what types of tissue it has spread eg lymph nodes, bone or soft tissue organs like the liver and lungs .

M0

No distant metastases (there is no evidence that the cancer has spread)

M1 –There is evidence of distant metastases

M1a –There is evidence that the cancer has spread to nonregional lymph nodes

M1b –There is evidence that the cancer has spread to bone(s)

M1c –The cancer has spread to other sites with or without bone disease

The different stages of prostate cancer

Localised Prostate Cancer

Prostate cancer that is still contained within the prostate is classified as localised prostate cancer. However, localised prostate cancer is further classified into different risk categories based on factors such as PSA levels, the Gleason score and the tumour grade. This is important, as the treatment options available may differ depending on the risk stratification. Different professional societies use different risk stratifications.

EAU Risk Stratification for biochemical recurrence of clinically localised prostate cancer based on the Gleason score and tumour stage assessed by digital rectal examination.

Low Risk – localised prostate cancer

PSA <10 ng/ml

Gleason ≤6 and ISUP Grade Group 1

T stage: T1 - T2a

Intermediate risk – localised prostate cancer

PSA 10-20 ng/ml

Gleason 7 and ISUP Grade Group 2/3

T stage: T2b – T2c

High risk – localised prostate cancer (also referred to as locally advanced prostate cancer)

PSA >20 ng/ml

Gleason 8-10 and ISUP Grade Group 4/5

T stage: T3a

The NNC provides a more detailed classification of risk groups

| Risk Group | Clinical/Pathologic Features | ||

| Very low | Has all of the following:

• cT1c • Grade Group 1 • PSA <10 ng/mL • Fewer than 3 prostate biopsy fragments/cores positive, ≤50% cancer in each fragment/corea • PSA density <0.15 ng/mL/g |

||

| Lowf | Has all of the following but does not qualify for very low risk:

• cT1–cT2a • Grade Group 1 • PSA <10 ng/mL |

||

| Intermediatef | Has all of the following:

• No high-risk group features • No very-high-risk group features • Has one or more intermediate risk factors (IRFs): ► cT2b–cT2c ► Grade Group 2 or 3 ► PSA 10–20 ng/mL |

Favourable intermediate | Has all of the following:

• 1 IRF • Grade Group 1 or 2 • <50% biopsy cores positive (eg, <6 of 12 cores)a |

| Unfavourable intermediate | Has one or more of the following:

• 2 or 3 IRFs • Grade Group 3 • ≥ 50% biopsy cores positive (eg, ≥ 6 of 12 cores)a |

||

| High | Has no very-high-risk features and has exactly one high-risk feature:

• cT3a OR • Grade Group 4 or Grade Group 5 OR • PSA >20 ng/mL |

||

| Very high | Has at least one of the following:

• cT3b–cT4 • Primary Gleason pattern 5 • 2 or 3 high-risk features • >4 cores with Grade Group 4 or 5 |

||

Biochemical Recurrence ( A rising PSA after treatment of localised prostate cancer)

Men who have been treated for localsised prostate cancer with radiotherapy (brachytherapy or external beam radiation) or who have had a radical prostatectomy will have to go for regular PSA tests. A rising PSA level can happen months or many years after treatment and is usually the first indicator that the cancer may be recurring. If imaging test show no signs of the cancer spreading then this is referred to as biochemical recurrence. Biochemical recurrence may precede imaging findings or symptoms of active disease by months or even years.

The PSA levels that define recurrence are determined by the type of treatment a patient has previously received.

Biochemical recurrence after a radical prostatectomy

In patients who have had a prostatectomy, the PSA levels should fall to undetectable levels ie. below 0.1ng/ml.

This is called PSA nadir or the lowest level of PSA. If the PSA levels increase and reach a level of 0.2 ng/ml or more on two consecutive occasions then this is regarded as recurrent disease.

Biochemical recurrence after radiation therapy

Monitoring PSA levels in patients after radiation therapy is more complicated as the PSA doesn’t reach undetectable levels as with

surgery, because some prostate tissue remains. PSA levels decline gradually after treatment and it can take 18 months or even longer for the PSA to reach the lowest levels (PSA nadir). In patients who have had external beam radiation or brachytherapy, a PSA rise of 2ng/ml above nadir (the lowest PSA level reached after therapy) is indicative of recurrence.

Cancer progression after biochemical recurrence

Biochemical recurrence doesn’t necessarily predict the development of metastases. Several other factors affect how quickly the cancer is likely to progress as well as the type of treatment that may help

Metastatic Prostate Cancer

Prostate cancer is classified as advanced or metastatic if:

The cancer has spread to non-regional lymph nodes

and/or the cancer has spread to bone

and/or the cancer has spread to other sites with or without bone disease.

There is no cure for metastatic prostate cancer, however there are an ever increasing number of treatments that can help slow the progression of the disease and even delay the onset of symptoms caused by the cancer.

The number and location of the metastases will have an impact on how long patients are likely to survive. Patients with only bone metastases tend to live longer than patients with visceral metastases (cancer that has spread to organs such as the liver, kidneys etc).

Lower risk metastatic prostate cancer (oligometastatic prostate cancer)

This is a relatively new definition which describes a prostate cancer that is between localised and widespread metastatic prostate cancer. It means that the cancer has not spread widely. There is no agreement on the number of sites that it has spread to and definitions vary between 3 and 5 metastatic sites that affect only bone and or lymph nodes. The cancer appears to be more slow growing than the usual metastatic prostate cancer. Treatment is aimed at the sites of the mettases.

References:

- Prostate Cancer: Stages and Grades. Cancer.Net Editorial Board, 11/2019. Available at: https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/prostate-cancer/stages-and-grades

- AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. Seventh Edition 2010. America Joint Committee on Cancer. Springer.

- Coetzee L. Metastatic Prostate Cancer. Health Press Limited 2017.

- Klaassen Z. The Impact of Visceral Metastasis in Prostate Cancer Patients. Urotoday. Available at: https://www.urotoday.com/library-resources/mcrpc-treatment/111525-the-impact-of-visceral-metastasis-in-prostate-cancer-patients

- Oligometastatic Prostate Cancer: A Shrinking Subset or an Opportunity for Cure? Rao et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology 2019.

- Muambirwa S. Understanding Recurrent and Metastatic Prostate Cancer. Feb 2022. MedEd/Ronin-Do (Pty) Ltd.

- EAU Guidelines. Edn. presented at the EAU Annual Congress Milan 2023. ISBN 978-94-92671-19-6. Available at: https://uroweb.org/guidelines/prostate-cancer/summary-of-changes/2023

- Schaeffer EM, Scrinvas S, Adra N, et al. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines). Prostate Cancer. Version 4.2023 – 7 September. 2023.

A prostate cancer diagnosis – what now?

Updated 25 June 2024

Being diagnosed with prostate cancer inevitably comes with a sense of shock and even fear. It can be an overwhelming and confusing time with the overriding question often being “What now?”. First off, take a deep breath or two to assist with keeping the panic at bay. Remember that most prostate cancers are slow growing, meaning that you likely don’t have to make all of your decisions immediately. Take time to consider the following suggestions:

Educate yourself

If possible read up on prostate cancer or speak to other prostate cancer patients in order to improve your understanding of the disease as this can be helpful in separating fact from fiction. It is important that you deal with fact. Be aware of “Dr Google” as reading up on medical facts without the requisite medical knowledge can be alarming and confusing.

Prepare for your next doctor’s appointment

Your doctor will likely cover the specifics of the cancer that you have and will undoubtedly tell you about treatment options which could include active surveillance (‘watching and waiting’), surgery, radiation therapy, hormone therapy, chemotherapy or even a combination of these . This can be a lot of information to take in at once so, if possible, have a notepad and pen with you so that you can jot down notes that you can look over later.

If possible take a friend or family member along with you. Not only does this provide you with some support but having another listening ear can also be helpful when there is a lot of information to absorb.

Have a list of questions written down that you would like to ask your doctor. These could include:

- Is the cancer localised or has it spread to other parts of the body (metastatic prostate cancer)?

- Is the type of cancer that I have curable?

- Will further tests be needed? If so, which tests? And who will be available to explain to me what the results mean?

- What are all my treatment options?

- What factors should I consider when choosing a treatment?

- What is your experience with these treatments?

- When can the treatment begin and for how long will it last?

- What are the possible side effects of and/or risks associated with the various treatment options? Could these include incontinence, erectile dysfunction, loss of sex drive, pain? If so, how do I best manage these?

- How will the treatment affect my quality of life?

- If surgery is an option what all does the surgery involve and what would the hospital stay entail?

- Is active surveillance an option for me? If so what does it involve and how often will I need to be checked? What should I be looking out for?

- What if the cancer spreads?

- What other health professionals will be involved in my treatment and care – oncologists, nuclear medicine physicians, psychologists, physiotherapists, anesthaesiologists?

- What outcomes can I realistically expect from a specific treatment option?

Request a copy of all your lab results and any other tests that are done and keep these in a safe place. They are useful to have if you want another opinion and if you do any of your own research. However always speak to your specialist before you reach any conclusions on your own.

Find the right doctor

If you have a private medical aid you should try to find specialists that you are comfortable with and that you feel you can trust. You’re going to see him/her frequently over an extended period of time, you may as well like him and feel a ‘right fit’ with him.

Initially you will probably be referred to a urologist who will make the diagnosis. Depending on how the cancer is going to be treated you may also be referred to an oncologist, a radiation oncologist or even a nuclear medicine physician. Other healthcare professionals like physiotherapists and sexologists might also assist you at different stages of your treatment.

If you have a family doctor/GP they can help you find a specialist.

Seek a second opinion if necessary

Your health and your treatment are your responsibility. If you are not happy with the advice you are receiving from your doctor seek a second opinion. Do not be concerned about possibly offending your doctor, it is your right to seek out the help you feel you need.

Don’t try and do it alone

This can be a scary time and it is important to draw on all the resources and support structures available to you. Talk to someone – whether it be your partner, a friend, a family member or a professional such as a nurse or a counsellor or a psychologist. Share what you are thinking and feeling. You may well be feeling anxious about the future and about the impact of your illness on the relationships with the people close to you. Talking about these things is not a cure but it will definitely help you feel less burdened and will assist you in processing the confusing thoughts and feelings.

You may well find that your loved ones are as confused and anxious as you are. Their personal discomfort and fear might mean that they find it too difficult to even acknowledge your illness, let alone talk about it. They will not necessarily know how to support you. Be direct and honest about what you need from them and how they can help you. Don’t expect them to be able to read your mind.

Join a support group or talk to a prostate cancer survivor

Becoming part of a group of men who are going through a similar experience to you can be tremendously helpful. It provides you with an opportunity to ask questions and express concerns to people who understand exactly what you are going through. The Prostate Cancer Foundation of South Africa runs an email support group.

Take care of yourself

Do whatever you can to maintain your health. Explore stress management and relaxation techniques. Eat well, remain as active as possible, and get sufficient sleep. Set your own pace. Yes, you have cancer but try not to allow the diagnosis to define you. Pursue your hobbies and interests and maintain your friendships. Talk about things other than your disease. Set yourself achievable goals, schedule things that you can look forward to.

Seek emotional help if you need it

If you continue to feel overwhelmed and are simply not able to shake anxious and depressive thoughts and feelings, seek help from a professional. Getting help is a sign of strength. It is important to take control of the things that you can take control of.

Treatment options for localised prostate cancer

Updated 28 June 2024

If you have been diagnosed with localised prostate cancer there may be various treatment options available to you. Prostate cancer that is diagnosed when it is still localised can be cured. Before deciding on what treatment will be best suited to you, your doctor should assess your life expectancy, health status, frailty and co-morbidities. If your life expectancy is less than 10 years you will be unlikely to benefit from active treatments.

The decision on what treatment will be best for you should be made jointly by you and your doctor. You should be fully informed of all treatment options available to you for your stage of prostate cancer, even if these are not provided by the specialist that you are consulting. You need to ensure that you fully understand the advantages and disadvantages of all the treatment options and their potential impact on your quality of life, in order to make an informed decision. Prostate cancer is usually a slow growing type of cancer, so you should take your time to understand the side effects of the different treatment options before you make your decision. It’s a good idea to speak to other men who have been in your position before you make your decision. You can do this by joining the Prostate Cancer Foundation’s email support group which is made up of men who have had various treatments.

Treatments options include monitoring the cancer or active treatments

Monitoring the cancer

- Active surveillance

- watchful waiting

Surgical treatments

- Open radical prostatectomy

- Laparoscopic prostatectomy

- Robotic assisted Laparoscopic prostatectomy

Radiation Treatments

- Radiotherapy options include

- External beam radiotherapy (EBRT)

- Brachytherapy (BT)

- A combination of EBRT, BT and androgen deprivation treatment

References:

1 Mutambirwa S, Coetzee L, Adam A et al. Prostate Cancer Foundation screening guidelines. Available at: https://prostate-ca.co.za/for-healthcare-professionals/.

ACTIVE SURVEILLANCE FOR LOCALISED PROSTATE CANCER

Updated 28 June 2024

Active surveillance aims to avoid unnecessary treatment and spare men from the side effects of these. Men are closely monitored with the objective of intervening timeously if there is disease progression to ensure that active treatments are still potentially curative.

Patient selection for active surveillance

Not all types of localised prostate cancer are suitable for active surveillance. Only men with low risk disease or favourable intermediate risk disease with no adverse risk features are suitable candidates.

Factors that may exclude men as candidates for AS include:

- extensive disease on MRI

- high PSA density

The following features found on the biopsy also mean that these men are not suitable candidates:

- predominant ductal carcinoma (including pure intraductal carcinoma)

- cibriform histology

- sarcomatoid carcinoma

- small cell carcinoma

- extra capsular extension

- lymph node vesicle invasion in needle biopsy

- Perinural invasion

- High risk disease

For men with very low risk disease, the 2024 NCCN guidelines now recommend that active surveillance should be the treatment of choice. The NCCN define very low risk disease as; PSA level <10 ng/mL, 3 prostate biopsy fragments/cores positive, <51% cancer in each fragment/core, and a PSA density of 0.15 ng/mL/g.)

If you do choose active surveillance, you will need to be regularly monitored to ensure that any disease progression is picked up so that an active treatment can be given before the cancer spreads.

The NICE protocol is one way of monitoring patients on active surveillance

| Timing | Test |

| When starting active surveillance | Multiparametric MRI if not previously performeda |

| Throughout active surveillance | Monitor changes to the PSAb |

| Year 1 of active surveillance | Every 3–4 months: measure PSA

Every 6–12 months: perform a digital rectal examination (DRE)c At 12 months: do a prostate biopsy |

| Years 2–4 of active surveillance | Every 3–6 months: measure PSA

Every 6–12 months: perform DRE |

| Year 5 and every year thereafter until active surveillance ends | Every 6 months: measure PSA

Every 12 months: perform DRE |

aIf there is concern about clinical or PSA changes at any time during active surveillance, reassess with multiparametric MRI and/or rebiopsy.

bMay include PSA doubling time and velocity.

cShould be performed by a healthcare professional with expertise and confidence in performing DRE.

Advantages of active surveillance

- You avoid the side effects of active treatments which can significantly affect your quality of life

- Active surveillance won’t affect your everyday life as much as active treatment might

- If tests show that your cancer might be growing, you can still have active treatments that aim to cure your cancer

- In a clinical trial called the ProtecT trial, the number of men with very low risk prostate cancer who died after 10 years following active surveillance compared to men who had a prostatectomy or radiation therapy was very similar

Disadvantages of active surveillance

- You will need to have more prostate biopsies

- Your general health could change, which might make some treatments unsuitable for you if you did need them

- Some men struggle with the anxiety of knowing that they have untreated cancer in their body

- In a small percentage of men who choose active surveillance the cancer spreads spreads , which means that it may no longer be curable

- In a trial comparing men who had low risk prostate cancer after 15 years, more men in the active surveillance group developed distant or regional node metastases compared to men who had a radical prostatectomy or radiation therapy:

9.4% compared with 4.7% in the radical prostatectomy group and 5.0% in the radiation therapy group

References:

1 Mutambirwa S, Coetzee L, Adam A et al. Prostate Cancer Foundation screening guidelines. Available at: https://prostate-ca.co.za/for-healthcare-professionals/.

2 Schaeffer EM, Srinivas S, Adra N, et al. Natl Compr Canc Netw 2024;22(3):140–150. Prostate Cancer, Version 3.2024 Featured Updates to the NCCN Guidelines.

Surgical Treatment for Localised Prostate cancer

Compiled July 2020

Surgery to remove the prostate is called a radical prostatectomy. The entire prostate gland, the seminal vesicles and some adjacent tissue are removed during surgery. In patients with intermediate or high risk localised prostate cancer, some of the lymph nodes may also be removed.

One of the advantages of surgery is that the entire prostate, the seminal vesicles and some of the surrounding tissues are sent to a pathology laboratory and analysed. This provides an opportunity for the prostate cancer to be restaged (pathologic staging). This type of staging is more accurate than clinical staging and you may be given a new Gleason score and tumour stage. If the pathologic staging and the surgeon’s observations show that the cancer is more aggressive than the original biopsy results showed, then your cancer may be reclassified as locally advanced and your urologist may recommend additional treatments.

Prostate cancer surgery is a major operation and, as with all surgery, there are risks that men need to be aware of. These include complications from a general anaesthetic, blood loss and the need for a blood transfusion (this is more common with open surgery), pulmonary embolism and wound infection.

The challenge with prostate cancer surgery is to remove all of the cancer whilst minimising damage to the nerves that enable men to have erections and also preserving the structures and nerve supply that are involved in bladder control (continence). Part of the procedure involves cutting the urethra just below the bladder in order to remove the prostate gland. This results in the removal of one of the sphincters (the internal urethral sphincter) that assists with bladder control (continence). The urethra is reattached to the bladder after the prostate has been removed and a catheter is kept inserted to allow the join to heal without forming scar tissue (which can result in narrowing of the tube). The catheter is a tube that drains urine from the bladder through the penis and into a bag. The catheter may be kept in place for a few days or weeks depending on the type of surgery. The two tubes carrying sperm from the testes (vas deferens) are also cut so men will be infertile after the procedure.

Nerve-sparing surgery

There are two main nerve bundles running along the sides of the prostate. These are the nerves that enable a man to have erections and they also play a role in bladder control (urinary continence). Urologists will try to preserve the nerves (a nerve-sparing prostatectomy) but this is not always possible. If the cancer has invaded the nerves they have to be removed. Even if the nerves are not removed there is a chance that they may be damaged during the surgery.

This is why erectile dysfunction is a common side effect of surgery. Full recovery of erectile function is more likely in younger men who had good erectile function before surgery and where the nerves on both sides of the prostate have been preserved. Recovery of continence is also significantly better in men who have had a nerve sparing procedure.

Types of radical prostatectomies available

Irrespective of the type of surgery you undergo, research has consistently shown that the best outcomes are achieved by surgeons who are doing high numbers of prostatectomies.

Open radical prostatectomy (ORP)